Church-Turing Thesis

In the previous section, we looked at what exactly a Turing Machine (referred to as a "TM" henceforth) is and alluded to the Church-Turing Thesis which states the following:

If any algorithm can be performed on any piece of hardware there is an equivalent algorithm for a Turing Machine which will perform the exact same task

The acceptance of this thesis has the following effects:

- Any problem that cannot be computed by a TM is not "computable" in the absolute sense

- If a problem is believed to be computable, a TM capable of computing is possible

With the feasibility of computation being well defined, computer scientists were also concerned with efficiency, that is, how long as well as how much memory would some problem need in order to be computed. 1

Complexity-Theoretic Church-Turing Thesis

In the 1960s and 70s, a number of observations about the efficiency of algorithms on non-TM models of computation led to the creation of a "strengthened" Church-Turing thesis, more formally known as the "Complexity-Theoretic Church-Turing Thesis".

It states the following:

Any algorithmic process can be simulated efficiently using a TM

This property arises from the fact that any algorithmic process that could be solved in another model of computation can be SIMULATED on a TM.

The "efficiently" in the thesis means that the number of operations (or other resource consumed like memory) it takes to run an algorithm grows polynomially (or less) relative to the size of data inputted. This idea of efficiency (data input size vs growth of the number of operations) will be explained in more detail in the next section and formalized considering that this is the universally accepted way of defining an algorithm's complexity. 2

Challenges to Complexity-Theoretic Church-Turing Thesis

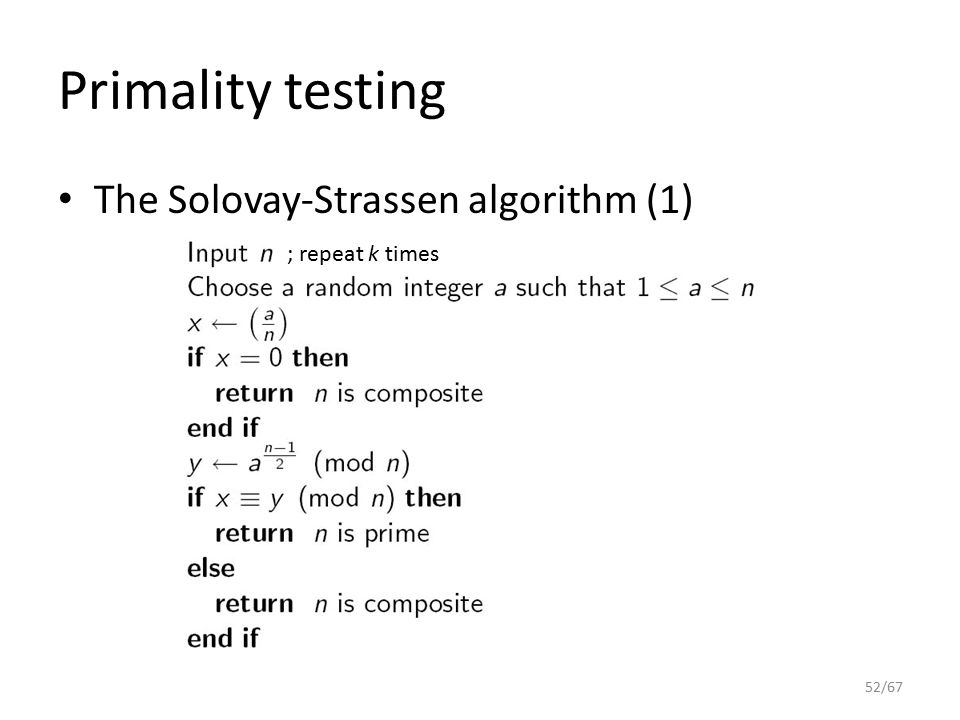

In the mid-1970s, an algorithm created by Robert Solovay and Volker Strassen known as the Solovay-Strassen Test challenged the Complexity-Theoretic Church-Turing Thesis by given an algorithmic process THAT COULD NOT be simulated efficiently using a Turing Machine.

The Solovay-Strassen test can probabilistically determine whether or not an integer is prime. Probabilistically means that even when the algorithm tells you an integer is prime or not, there exists the possibility that result is incorrect. However, if you repeatedly run the test, you can decrease the uncertainty to a desirable point and get closer to a more accurate result.

The steps for the entire algorithm are presented below. Don't concern yourself too much with anything beyond the first three lines.

Source: Public Key ciphers 1 Session 5. by Katrina Morrison

Note the step:

Choose a random integer a such that \(1 \le a \le n\)

The "random" part here is troubling because there exists no efficient method of choosing a random integer on a TM, especially not a truly random integer.

Beyond the TM

To be more specific, there is no efficient method on a Deterministic Turing Machine. The TM that was presented to you in the "Turing Machine" section is a Deterministic Turing Machine (now referred to as a DTM henceforth) because each symbol on the tape refers to one and only one course of action (move one cell left/right, erase, write, etc.).

There does however, exist an efficient method on a Probabilistic Turing Machine which chooses between possible actions according to a probability distribution rather than a fixed set of instructions. The probabilistic TM falls into a class of TMs known as Non-Deterministic Turing Machines (referred to as a NTM henceforth) which, instead of having one symbol correspond to one course of action, can have them correspond to a set of different actions from which one is chosen through some procedure.

With the Probabilistic TM, the Complexity-Theoretic Church-Turing thesis was revised to the following:

Any algorithmic process can be simulated efficiently using a probabilistic Turing Machine

Thereby allowing the Church-Turing thesis to maintain its efficiency over such algorithms as the Solovay-Strassen test and anything that requires non-deterministic operations (such as choosing a random integer).

Dawn of Quantum Computing

Solovay-Strassen wouldn't be the only challenge to the Complexity-Theoretic Church Turing thesis. Due to the revision of the thesis from a normal TM to a probabilistic TM, computer scientists wondered if there was some "ultimate" thesis, one that would encompass all simulations of other models of computation efficiently. Motivated by this, in 1985 the British physicist David Deutsch attempted to come up with a computational model that would allow one to simulate ANY arbitrary physical system. Due to the ultimately Quantum Mechanical nature of the physical world, Deutsch posed the idea of computing devices based on quantum mechanics.

In the same decade as Deutsch, Richard Feynman also proposed the idea of Quantum Computing for simulating physical systems, namely, the Quantum Many-Body Problem where due to quantum entanglement between microscopic particles (which you'll be introduced to in more advanced sections), the amount of information required for a classical computer to handle is too prohibitive and we must instead, use approximations.

Onwards to Motivations for Quantum Computing

Despite all these definitions, we still haven't reached the promised goal of understanding WHY we want Quantum Computing (other than Feynman's and Deutsch's goals). We do however, have an understanding of how the principles of classical computation have naturally led to the idea of Quantum Computing.

In the following section, you'll be introduced to the ideas and some light math behind Computational Complexity which is how we characterized the performance of algorithms and Complexity Classes, where we categorize problems by how much time and space they take to solve.